There are lots of approaches and scales that make housing affordable and equitable. The National Building Museum is wrapping up an exhibition on housing. Many of the project types below are catalogued in the exhibit. One exhibit, the Open House, by architect Pierluigi Colombo, is a full size mockup of a super-efficient and flexible living space designed to accommodate a variety of housing needs within one space.

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADU) are most recognized as backyard garages turned into apartments. ADU’s are an easy way to increase density without disrupting the existing fabric of neighborhoods. It also allows individual property owners to develop their property, realizing economic gain through rental income. Longtime residents can offset increases in cost of living in gentrifying areas through this income. Populations vulnerable to displacement can remain where they are.

Unfortunately, ADU’s are prohibited by most zoning codes which have most recently (but not historically) favored single family structures. California has led the way recently in changing this approach by rewriting their laws regarding ADU’s. Between 2010 and 2016, Portland, Oregon led the ADU movement, issuing 2000 permits – 600 of those in 2016 alone. Zoning considerations included easing setbacks and design standards and allowing short term rentals.

Other challenges in developing ADU’s include limited access to financing, tight construction sites and existing infrastructure and utilities that interfere with new construction. Kasita prefabricated modular units to facilitate construction (just drop them in) or developing prefabricated modular service cores (bathrooms/kitchens) to reduce the costliest of construction activities by building offsite in controlled environments. Rice University’s Architecture Construct is engaging future architects and planners in deeper discussions of architecture and housing. Modative Architects markets ADU designs and garage conversions. United Dwelling helps with financing and builds ADU or garage units, splitting the rent with the landowner to cover costs in a lease arrangement. With a vision that development should be equitable and self-directed, La Mas developed the Backyard Homes project in Los Angeles. Property owners that were asset rich, but cash poor become Section 8 landlords. La Mas provides pro bono project management and discounted design/construction services and flexible financing. Construction is scheduled to begin in 2019. Similarly, The Alley Flat Project in Austin, Texas incentivizes the development of affordable accessory dwellings, providing project design and management assistance and a reduction of fees.

Bridge Housing is a concept of providing transitional housing - a conceptual “bridge” between emergency sheltering and permanent housing. In April 2018, Mayor Garcetti of Los Angeles and the City Council declared an emergency shelter crisis and took advantage of a new state law that enables cities to construct bridge housing — faster than ever before — on any land owned or leased by the City. El Pueblo Emergency Shelter built the first shelters of this program, installing three trailers around a communal deck space to provide accommodations for 45 people in Los Angeles, providing community and belonging in addition to accommodations. The Urban Land Institute is investigating further, pairing architects and landscape designers to create installations through half day charettes. Three installations are expected to be implemented in July. A broader summary of their involvement with bridge housing is available here.

Size of accommodations is another aspect of housing that’s being questioned in the pursuit of affordability. How much space do we need to live? Although the most expensive components of living (kitchens and bathrooms) are still present, smaller homes allow more living space to be built on the same land. As land costs increase, the ability to build more housing in the same land area can potentially reduce costs. Similar to ADU’s, these “Tiny Homes” may provide more equitable access to those with limited means to invest in housing by decreasing the investment required. Also, like ADU’s, many zoning laws and building codes require minimum square footages, mass and height of new structures and do not permit “tiny homes”.

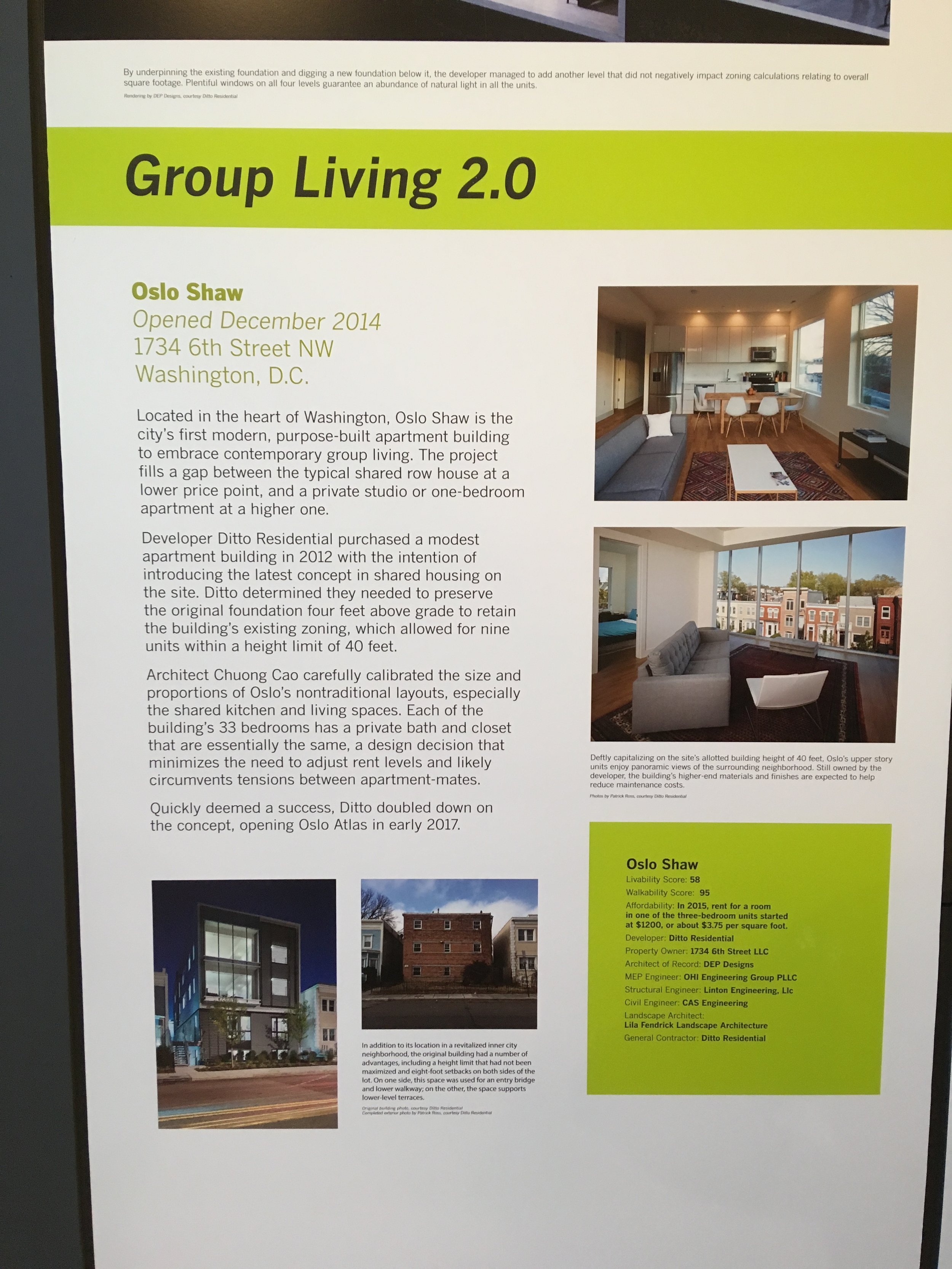

Co-Living arrangements provide dorm style living where private sleeping spaces share communal spaces for living, eating and sometimes bathing. The more expensive aspects of residential construction and maintenance (kitchens and bathrooms) are spread among multiple living units, increasing affordability. While there are no limits on related individuals, many zoning codes limit the number of unrelated individuals that can live in a single dwelling. These rules favor traditional nuclear families and limit the development of communal housing. Oslo Shaw is Washington DC’s first purpose-built co-housing building. Each of the 33 bedrooms has a bath and closet but shares communal spaces. WeWork is getting in on the act by developing WeLive concept. WeLive Crystal City is in Arlington, Virginia and offers over 200 units between 300 and 800 square feet. In Vermont, Home Share Now is developing co-living arrangements for the elderly, who want to remain in their house, but may have financial or maintenance challenges. The program matches those seeking living space with those who have extra living space. CoAbode and Nesterly match those seeking housing, providing co-housing arrangements for those that might need support services like single mothers or those looking to manage housing costs by splitting expenses or owners needing help with maintenance of their homes.

Other housing concepts include Ownership co-ops where multiple individuals own property and conversions of motels into housing. Companies like Kasita are investigating ways to increase density by designing stackable prefabricated structures. In addition to prefabrication, new technologies like 3d printing are also being explored. New Story Charity says it can build a 650sf house for $10,000 using this new technology. Blokable offers a 328sf cottage for $60,000.

Many communities are adapting existing structures for new uses. Built in 1828, the Arcade is the nation’s oldest indoor shopping mall and remains the historic heart of Providence’s downtown. Today it is a mixed-use development containing 48 affordable micro-units ranging from 225 to 300 square feet.

Let’s look at some case studies from cities where these alternate housing options are making a difference:

Oakland has been referred to as San Francisco’s Brooklyn. Gentrification driven by growth in technology sectors threatens its quirky, unique and inclusive community. As Silicon Valley gets closer, living in Oakland becomes more appealing to the young workforce seeking out an authentic scene. As gentrification has increased, so has the stark disparity between affordable and market rate housing options. Adopted in 2015, the Oakland Housing Cabinet report outlines a roadmap for equitable housing solutions. Goals include encouraging new development, streamlining the permitting process, but also protecting households vulnerable to displacement, easing restrictions on ADU’s, instituting rent control measures, helping non-profits interested in buying and preserving affordable units, providing incentives for Section 8 landlords, and exploring community land trusts. One interesting approach to serving those without homes in their community was to re-purpose garden sheds for use as shelters in a homeless encampment under a freeway. Not uncommon to many communities, efforts are often confronted by an ethos of obstruction – particularly against development, density and destruction of open land. Meanwhile, the economy and worker populations keep growing. Much faster than housing options.

New York has experienced the largest proportional rent increase - 45% in poor neighborhoods between 2010 and 2018, while rent in higher districts remain relatively stable at 16% over the same time period. The growth of Airbnb has taken many units off the market, compounding the problem. While rent stabilization helps with costs, it stresses out tenants – who often feel like the buzzards circling waiting for them to leave (voluntarily or coerced through slow repairs or adverse living conditions). The city is investigating innovated approaches like limited equity co-op housing (buy low, sell low), micro-units, legal assistance for eviction issues, legalizing basement apartments, building in open parking lots (increasing density on open land), and building to high energy standards to reduce utility costs and encouraging mixed income developments. The city has tried rezoning for denser affordable housing but found this often displaces existing low-rise commercial buildings serving the existing population. Displacement may happen regardless however (see gentrification) and at least this effort ensures some intent of affordability. Habitat for Humanity is developing ownership co-ops like Sydney House. These co-ops ensure a high level of stable affordability but limit the ability of folks to capture their “investment” in the same manner other homeowners would be able to. This city is also developing housing in existing lots and open spaces of housing projects owned by the Housing Authority. They are also reviewing the building codes, considering allowing basement apartments, which had previously been restricted by minimum requirements for ceiling heights and window sizes. The mayor waived requirements in a housing competition to create the Carmel Place project containing 55 units between 260 and 360 square feet. The city has found the square foot rents for some micro-units is nearly double the average and have sponsored design competitions to develop tiny homes on small and irregular city owned lots all over the city.

Orlando has experienced a disparity between wages of tourism industry workers and housing for those workers. Wages have not kept the pace of housing costs, which have increased due to demand by exploding population. Walt Disney world pays $10/hour. Using the 1/3 rule, this would support $580 in monthly rent or mortgage. Current average rents in Orlando $1200. The situation is exacerbated by outside investors who often aren’t tied to or impacted by local wage rates. Many of these investors grabbed up property during the housing market crash, spiking prices in the boom. Solutions the city is pursuing include converting underutilized motels into efficiency apartments, developing mobile home parks for rental/purchase, creating a land trusts in gentrifying neighborhoods to maintain longtime residents, investigating the use of shipping containers for shelter and developing inclusionary zoning to require a certain percentage of affordable units in new developments.

Minneapolis, according to some reports, just passed significant and historic zoning reform. Homes in the Twin Cities remain relatively inexpensive. But not for everyone. Minneapolis faces some of the worst disparities in the nation of racial and income inequality and access to housing and economic opportunities. Concentration of development is often in “hot” neighborhoods, allowing poorer neighborhoods to stagnate. Common to many communities, rents have increased with demand, while incomes have stagnated. The city has added 83,000 households since 2010, while building just 64,000 new homes. Demand is expected to increase; the city anticipates another 233,000 households by 2040.

The new zoning code influences what types of housing can go where. Zoning everywhere has historically favored single family residences, but only since the 1970’s. Prior to that, cities could evolve and fill in incrementally even as the city also expanded its borders. The proposal “up zones” the entire city, allowing every neighborhood to evolve gradually to the next increment of development (as opposed to concentrated large-scale housing developments). The comprehensive plan update would create new zoning categories across the city. Duplexes and triplexes will now be allowed in every neighborhood citywide, most of which were formerly reserved for nothing but single-family houses. In addition to denser housing development, the new rules would allow developers in most residential areas to build higher. Streets with access to consistent public transit service will also be allowed to build in greater heights and intensities, up to 4 stories in many locations and 6 stories closer to the city center. The proposal would also eliminate off-street parking requirements, which add to the cost of a new project without increasing density. The new code recognizes the importance of mobility, making more focused investments in housing within walking distance of transit systems.

Their plan is organic and incremental. Spread across the entire city, not just in the areas where it’s going to be easiest or face little opposition, or in areas where gentrification through increase development is a concern. Not unexpectedly, the process has been politicized. But as a renter and representative of the city’s South Uptown Neighborhood Association, told Minneapolis Public Radio “it’s no longer appropriate to fuss over a neighborhood’s character when new residents aren’t able to stick around long enough to build their own character.” There are critics on both sides of the argument and only time will tell if the plan will work.

There are a lot of ways that affordability can manifest itself in the architecture of our homes. The first step is reconsidering zoning laws that restrict a more comprehensive and broad approach.

Next week, we wrap up our housing series!